As a single mother living in poverty in a city known for its weak record of educating students of color, Kanesha Wingo realized her odds of finding success were slim. But with help from a learning center in her Milwaukee apartment complex, Wingo completed her college education, creating a foundation for herself and young daughter.

Wingo, 28, earned a bachelor’s degree in psychology, sociology and religious studies from Alverno College in 2013 and recently earned a master’s degree in business administration from Cardinal Stritch University. Wingo earned both degrees from the Milwaukee schools with the help of scholarships through the community learning center.

Wingo said she believes education is the key to avoiding “that stereotype, that statistic that I was kind of born into” — a young black woman living in low-income housing.

Experts say centers like the one at the neighboring Greentree and Teutonia apartment complexes in Milwaukee where Wingo lived offer a promising method, developed over the past two decades, of shrinking academic achievement gaps.

The challenge is daunting: As reported in the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism Children Left Behind series in December, Wisconsin has the largest disparity between the performance of black and white students in the country, the worst graduation rate for black students and the nation’s highest suspension rate for black students.

Greentree and Teutonia are two of six low-income housing sites run by Carmen Porco, an executive at the nonprofit Housing Ministries of American Baptists in Wisconsin. These properties, in addition to Northport Apartments and Packer Townhouses in Madison, are available through the national rental assistance program, commonly known as Section 8.

Under this housing voucher program, rent is based on ability to pay. Residents pay 30 percent of their income for rent and utilities, a number that fluctuates when income levels change. This ensures residents can still afford monthly payments, even if they have been laid off, take a job with lower pay or have to cut work hours.

To qualify for housing vouchers in Madison, family income for a family of three cannot exceed $37,200. In Milwaukee, a family of three must make $33,000 or less to qualify.

The group’s properties provide numerous services to the low-income residents, including child care, family literacy classes and after-school tutoring for residents of all ages. College scholarships for up to $1,500 each semester are also provided through the sites.

Funding for the programming and scholarships is generated on site from tenants’ rent, Porco said. The Northport learning center costs $237,000 and the center at Packer is $284,000 to run per year, which includes funding the scholarship program and staff payroll. The learning center shared by Greentree and Teutonia in Milwaukee costs close to $243,000 to operate, he said. About 670 students between ages 3 and 18 live at the six Madison and Milwaukee properties.

Such low-income housing sites in Madison and Milwaukee are working to break the link between poverty and poor academic performance.

“Coming to the center really helped me a lot,” said Wingo, who now works as Greentree-Teutonia’s leasing agent. “Education helps you gain skills, and it takes you places you probably wouldn’t (go) on your own.”

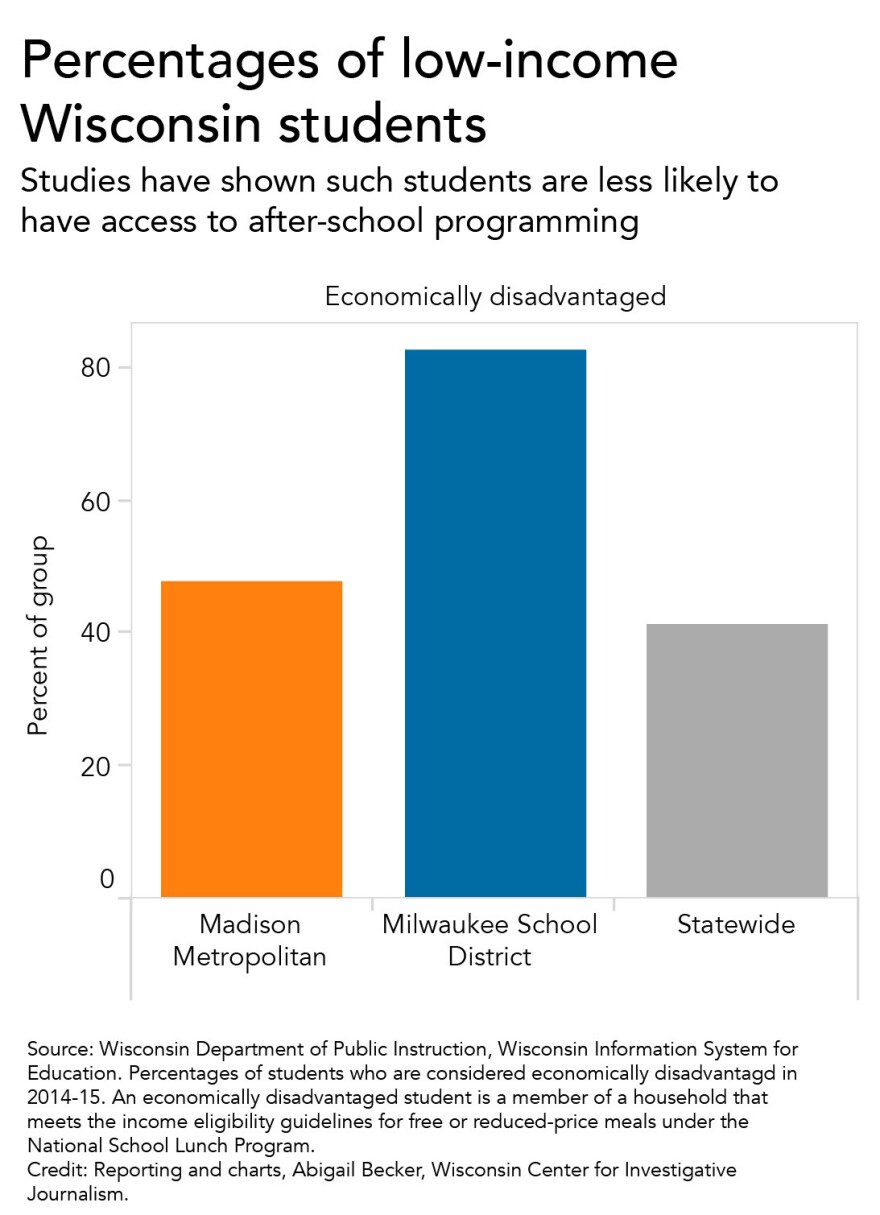

The number of poor Wisconsin students, measured by those who qualify for free or reduced-price meals at school, has risen significantly over the past decade, from 30 percent in 2005-06 to 42 percent in 2014-15. In Madison, 48 percent of students are considered economically disadvantaged; in Milwaukee the figure is 83 percent.

University of California-Irvine education researcher Deborah Lowe Vandell foundin 2013 that when elementary students consistently participate in after-school enrichment programs, achievement gaps in math between low-income and high-income students narrow.

“Education,” Porco said, “cannot just occur in the public schools.”

‘Home away from home’

Ien Roder-Guzman, 24, describes the learning center in the apartment complex where he lived as a “home away from home” that “kept my head focused on future stuff.”

Roder-Guzman grew up at the Packer Townhouses on Madison’s North Side and began going to the community learning center when he was 5. Despite moving around Madison and attending several schools, Roder-Guzman kept coming back to the learning center. He now works there part time.

Roder-Guzman graduated from Madison College in December with a two-year liberal arts degree that will help him transfer to a University of Wisconsin System school, but he said he also is considering joining the military. He said the learning center became a “main support system” for him while in school.

Data on Porco’s learning centers are limited. But what is available indicates students who are participating in the on-site educational programs are succeeding, said Charles Taylor, an education professor at Madison’s Edgewood College.

Taylor gathered data from students in Porco’s housing units and compared them to Madison and Milwaukee students overall. Although the sample size of 68 students was small, Taylor found that students living in the stable, low-income housing complexes exceeded their peers in each city when it came to academic performance and graduation rates.

From 2010-14, 97 percent of students in the study at the Madison properties graduated, and 100 percent of students in the study who lived at the Milwaukee properties graduated, Taylor found. The four-year graduation rate in the Madison district is 79 percent and Milwaukee’s is 61 percent.

“This is something that I believe is worth celebrating and duplicating,” Taylor said.

Eric Grodsky, an education researcher at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, acknowledged Porco’s work on Madison’s North Side “sounds amazing,” but without a more rigorous study of the program, it is hard to know the extent of the centers’ effectiveness.

“With a strong evaluation I think their work could benefit hundreds if not thousands of kids,” Grodsky said. “Without that evaluation, it’s a lot harder to get other entities to commit the sorts of resources necessary to do what they have done.”

Scholarships key to college success

Since 2006, the properties in Madison and Milwaukee have given out about $668,000 in scholarship money to more than 115 individuals. Residents pursuing undergraduate or master’s degrees said the scholarship and rent-assisted housing were critical to completing their degrees.

Wanda Melton, 33, who has a 12-year-old daughter, is a school counselor at Northwest Catholic School in Milwaukee. She completed her bachelor’s degree in psychology at Upper Iowa University in 2010 and earned her master's degree in school counseling at Mount Mary University in 2014 while she was a resident of Greentree-Teutonia.

While she was completing her counseling degree, Melton said she was required to complete an internship and had to take an unpaid leave of absence from her job.

“I definitely was able to lean on the scholarships,” Melton said.

Jean Knuth, Greentree-Teutonia’s housing manager, said the learning center has turned the complex into a community that meets many needs. There is child care, tutoring for students and a computer lab that helps residents search for jobs or write resumes.

“We can’t fix everybody and we can’t fix all of their children, but we can do something,” Greentree-Teutonia program director Vicki Davidson said. “All they have to do is let us know what they need.”

Stanford University professor Sean Reardon, who has studied racial achievement gaps, concluded that schools alone can reduce such disparities but they cannot eliminate them because of larger socioeconomic disparities.

That is where Porco’s “anti-poverty” housing model may come in. Porco began his experiment after taking over several low-income housing sites in 1974 — including Packer and Northport in Madison and Greentree-Teutonia in Milwaukee. Porco said he aims to fill a “community gap” by making services readily available rather than waiting for residents to seek them out.

Susan Goetz, an instructor with Madison College, teaches adult basic education and GED classes at Packer and English as a second language at Northport in Madison. She works with adult students who did not make it through high school and are “already at a disadvantage.”

“I try not to let people give up,” said Goetz, who has worked at the learning center for 17 years.

June Johnson, a Northport resident, is among those who did not give up. In 1989, after a divorce, Johnson moved into the low-income apartment complex with her three children. She began working at the learning center eight years later.

Johnson attended but did not graduate from Madison East High School and eventually earned her high school equivalency degree through the learning center.

“(The center is) a great salvation for some people, and I was one of them,” Johnson said.

Unstable housing, poor performance tied

Housing instability is another barrier to school success. Thousands of Wisconsin students have no permanent home.

In the 2014-15 school year, there were at least 18,000 homeless students across Wisconsin — a number that has more than tripled since 2003-04. Among homeless students across the state, there are 14,294 students who share housing with other families, 333 who have nowhere to live, 2,271 living in a shelter and 1,409 living in a hotel, according to data from the state Department of Public Instruction.

Housing stability allows people such as Martinus Roper to form crucial bonds with struggling students. Roper is the assistant program director at Milwaukee’s Greentree-Teutonia community center. Roper, called “Mr. M” by the students, recently earned an associate degree in business management through Cardinal Stritch University classes at the learning center.

Roper grew up in the Greentree-Teutonia complex and said he can identify with many of the students. He grew up without a father and understands the importance of having a consistent adult presence in a child’s life.

“I kind of take that role of a dad, big brother, uncle, whatever you need me to be in that moment, because I know how much that means, especially going through that as a child,” Roper said.

Packer program director Jacki Thomas has seen generations of students grow up on the property and in the learning center. Her involvement at the center allows her to form important bonds that help students succeed.

“People need to feel known,” Thomas said. “No gaps in education are ever going to change without relationship.”

Eileen Guzman agreed. She said the Packer community center became a “pseudo-parent” to her son, Ien, who spent many hours in and around the center, safe under the watchful eyes of neighbors.

If the learning center was not available, Guzman said, “we would have lost a lot of kids.”

Housing with learning centers are in short supply

Unfortunately, these apartments are available to few people. Packer, which has 140 units, has about 34 families on a waitlist and 15 families living there who are waiting for a larger or smaller apartment, manager Sandra Willis said.

Of the adjoined Greentree and Teutonia apartment complex’s 328 units, the one- and three-bedroom apartment waiting lists are closed, property manager Jean Knuth said, and about about 60 families are waiting for a two-bedroom unit.

Both managers say one reason waiting lists are so long is that residents on average stay about five years, but some stay much longer — up to 20 years.

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.