One day last May, Latoya S. was walking her 6-year-old pit bull, Gucci, when he began to snarl excitedly at a strange man standing on the front porch of her brick, two-bedroom ranch home. As Latoya approached her home, the man spoke. “You Latoya?” She nodded.

The man came closer as the dog’s bark grew louder. He handed Latoya an envelope and said, “You’ve been served!” Latoya took the envelope and watched the man dash to an old, beat-up Ford Taurus. She pitched the crisp, white envelope into the bushes next to her front door and went in the house. She knew she owed a few thousand dollars to the Cash Store payday lending business in Grafton, and now she was being sued.

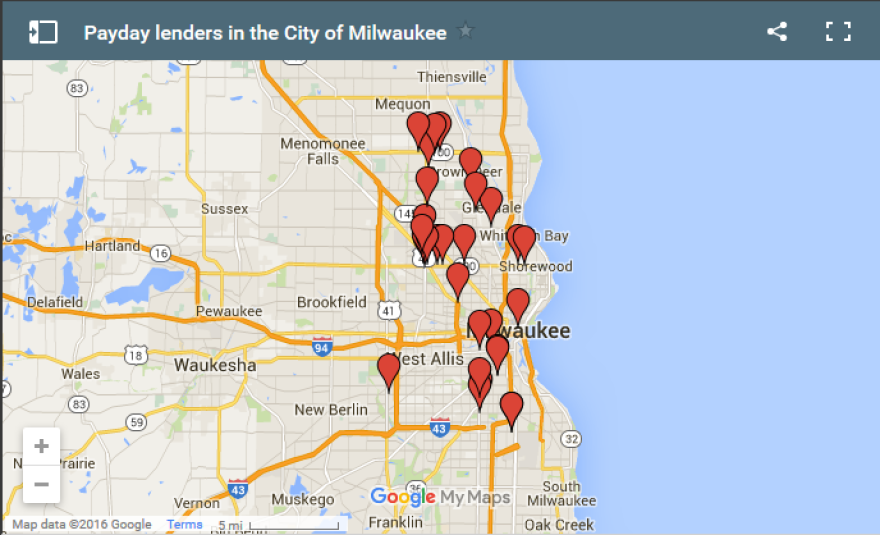

Latoya, who asked that her last name not be used, turned to the payday lender when she needed cash to pay her bills. And judging by the number of such operations in Milwaukee, there are many more people who find themselves in the same situation.

There are more payday lenders in Milwaukee as there are McDonald’s restaurants: 30 payday loan agencies inside the city limits and 25 McDonald’s, according to the corporate website. Check Into Cash, USA Payday Loans and Advance America are a few of the convenient cash businesses planted in predominantly African-American and Latino communities, where many consumers in a financial crunch turn when they need money.

The National Association of Consumer Advocates has deemed these businesses “predatory lenders.” Predatory lending is any lending practice that takes unfair advantage of a consumer by charging high interest rates and unreasonable fees and charges. Predatory lenders prey on minorities, the elderly, uneducated people and those who need quick cash for unexpected emergencies such as medical bills or car repairs.

Jamie Fulmer, senior vice president of public affairs for Advance America, takes issue with the term “predatory lenders,” blaming payday lending activist groups for misusing the label. “We offer consumers a product that is transparent and fully disclosed in the marketplace, and we do it in a simple, safe and reliable manner,” said Fulmer.

“If you peel back the onion and look at the actual facts associated with the products and services that Advance America offers, and you tie that together with the extremely high customer satisfaction and the low instances of complaints, I think it’s impossible to call us a predatory lender,” Fulmer added. Advance America runs 2,400 stores across the country.

No limit

Capitol Heights, Clarke Square, Sherman Park: payday loan agencies are scattered throughout communities occupied mainly by people of color. There are no licensed payday lenders in Whitefish Bay, Mequon, Brookfield, Wauwatosa, Shorewood, River Hills or Glendale.

“The only reason I believe some neighborhoods have these stores and some don’t is that the payday loan business owner wants to locate in poorer areas of the city,” said Patty Doherty, legislative aide to Ald. Bob Donovan. “People just are not very active and won’t bother to speak out against stores like this.”

According to Doherty, all payday loan stores in Milwaukee must get a variance, permission to deviate from zoning requirements, from the Board of Zoning Appeals. No areas in Milwaukee are zoned for payday loan businesses, so to open one the owner must convince the board that the business will not change the residential or commercial nature of the neighborhood.

Here’s how payday loans work: a customer who needs emergency cash takes out a short-term loan against his or her upcoming paycheck. In return, the person agrees to pay a high rate of interest on the loan. When the customer gets a paycheck, the agency automatically deducts the loan amount, plus a finance fee ranging from $15 to $30, directly from the customer’s checking account. The more money a customer borrows, the higher the finance charge.

Research conducted by The Pew Charitable Trusts in Washington, D.C., found that there are more payday loan stores per capita in Wisconsin than in most other states because its payday loan finance rates are so high, according to Nick Bourke, who directs Pew’s research on small-dollar loans.

“Wisconsin is one of seven states in the country that does not have a limit on payday loan rates. Right now, the typical payday loan in Wisconsin has an annual percentage rate (APR) of 574 percent, one of the highest rates in the United States — only Idaho and Texas have higher rates,” said Bourke.

“That rate is not just morally offensive to some, but it’s also far higher than necessary in order to make emergency credit available to people in need.”

‘Financial suicide’

Latoya, who grew up on the North Side of Milwaukee, came from a family where neither parents had a relationship with a bank. They both used local check-cashing stores to cash their bi-weekly paychecks. When a flier from Your Credit, a payday loan store on South 27th Street, came in the mail, Latoya decided to check it out. The flier promised quick cash, no credit check and lending options to build credit.

Latoya, then 19, was a freshman at UW-Milwaukee. She needed money for books and supplies, but didn’t want to ask her parents, who were already paying her tuition. Latoya went to the store and borrowed $75; two weeks later she paid back $150. Eighteen years later at age 37, she’s still paying off a payday lender after being sued for breaching the loan contract.

“Payday loan stores are parasites, period. In 2014, I took out a loan for $1,600, and ultimately had to pay back $5,000,” Latoya said. “They set up in the poorest neighborhoods in Milwaukee, preying on people who run into hard times. When your back is against the wall, trust me, you’ll do whatever it takes to keep your lights on, a roof over your head and food in your stomach.”

“Turning to a payday lender was financial suicide for me.”

It’s tempting to skip the small print on a lengthy payday loan contract, but for borrowers, those pages of legal disclosures are a must-read. The contracts reveal all the information that comes back to haunt borrowers later.

According to Amy Cantu, director of communications for the Community Financial Services Association of America, payday loan contracts guarantee that the lender is in compliance with the Truth in Lending Act (TILA), a federal law designed to protect consumers against unfair credit card and loan practices. TILA does not, however, place restrictions on how much a lender can charge in interest, late fees or other finance charges. The Community Financial Services Association of America represents payday lenders.

For nearly 20 years, Latoya continued to use payday lenders to help her out of ongoing financial difficulties. When she needed to replace the timing belt on her 1999 Chevy Malibu, she took out a $200 payday loan from Advance America, 8066 N. 76th St. When she got behind on her monthly car note and insurance payments, she borrowed $400 from ACE Cash Express, 1935 W. Silver Spring Drive.

“At one point, three cash stores were taking money from my checking account at the same time,” said Latoya. “That’s when I knew it was bad.”

Latoya didn’t limit her borrowing to in-store payday loan businesses; she also used online lenders. Online payday lenders offer the same services as in-store operations, providing an option for customers who prefer to submit a loan request through a website instead of in person.

“Once I discovered the online stores, I started using these exclusively,” she said “I knew online cash stores charged higher interest rates, but the process was quicker. I could fax or email my documents right from work and get the money the next day or in some cases, the same day.”

But according to a study by Pew Charitable Trusts, people who borrow money from online lenders are twice as likely to experience overdrafts on their bank accounts than those who borrow from a store. Plus, online-only lenders typically can avoid state regulations because the business operates entirely over the Internet.

According to Advance America’s Fulmer, “Much of the negative stigma associated with this industry stems from the online lenders that are not regulated at the state level. These businesses operate via the Internet, or some other offshore location, or in some cases they’re flat out scam artists,” said Fulmer. “There’s a difference between those of us who are regulated and audited by the state versus those lenders who aren’t.”

Payday loans are easier to secure than a traditional bank loan. According to PNC Bank’s website, to take out an unsecured loan, a customer would need proof of identification, bank account statements and recent pay stubs. A customer’s credit score can hinder the loan, and banks rarely make loan funds available the same day, or even within the same week.

“I applied for a loan from my bank and they denied me because of my debt-to-income ratio. The banker told me they prefer to loan larger amounts of money, repayable over time,” said Latoya, who has an active checking account with PNC Bank. “My bank couldn’t help me, so how else was I supposed to get groceries and pay my utilities?”

"When your back is against the wall, trust me, you''ll do whatever it takes to keep your lights on, a roof over your head and food in your stomach."

Customers can’t go to a bank and borrow $200, which is why Cantu believes payday lenders offer a valued service to people in the communities where the lenders operate.

“Banks aren’t going to fill this space,” said Cantu. “No one else is stepping up to offer short-term credit to this segment of the population that need it most. We have a vested interest in making sure our customers have a positive experience with a payday loan product. If we didn’t we wouldn’t be in business.”

Payday loans are made by private companies licensed by the Wisconsin Department of Financial Institutions (DFI), with lenders based in states including California, Illinois, Utah, Texas and Tennessee. In 2014, these payday lenders loaned more than $37.4 million to consumers in Wisconsin and made $8.4 million from fees and interest charges. The average loan was $320.

DFI data show that the number of loans made by payday lenders dropped 54 percent from 2011 to 2014, and the total amount of money loaned dropped 51 percent (see graphic, below).

According to Pew’s Bourke, payday lenders overall are making fewer loans with a longer duration. Several years ago a typical payday loan was due in two weeks, and most customers took out a second loan. Now, more payday lenders are giving customers four or six weeks to pay back a loan, reducing the number of loans.

“What we’re seeing is a lot of payday lenders starting to offer different types of high-rate installment loans,” said Bourke. “It can appear that that the loan usage is dropping off, but what’s happening is the average loan duration is going up.”

Cantu noted that demand for short-term loans is going up, but consumers have more credit options than they did five years ago. “If you look at the whole spectrum of short-term credit products, not just payday, you’ll see that consumers are borrowing more.”

Cantu added that efforts to regulate payday loans in Wisconsin have led to some reductions in the number of stores, which also helps explain the lower number of payday loans.

‘They make it so easy’

Latoya’s annual salary is $57,000. She’s worked for the same employer for 13 years, and recently took on an additional part-time job that allows her to work from home. She makes good money, so why has she depended on payday loans through the years? “Desperation,” she explained.

Every two weeks, Latoya would bring home a $1,700 paycheck after taxes. “My rent is $1,000, student loans are $594, my car note is $400 – that’s over $2,000 right there,” she said. “I still haven’t factored in utilities, car insurance, groceries or gas. I have no other option. I have no one to help me and they make it so easy to walk in the cash store, answer a few questions and walk out with cash money.”

In 2014, Latoya got behind on her bills. Her rent was due, the refrigerator was empty and her dog desperately needed to see the vet. To pay for the dog’s medical treatment, Latoya could either skip paying her bills that month, or take out another payday loan.

Latoya took out another payday loan.

This time she drove to the Cash Store in Grafton. There were no customers sitting in the lobby when Latoya walked in, she said. It was a small, clean business. The customer service workers greeted her instantly and with friendly smiles. She spoke with one of the workers who asked Latoya a series of questions, entering information into a computer and making phone calls to verify her employment and financial institution status.

After 10 minutes, a loan officer said Latoya could borrow $3,200. She decided to borrow $1,600. The loan officer was pleasant and went over the loan agreement thoroughly, she recalled. Latoya understood that even though she was borrowing $1,600, the contract clearly specified she would be responsible for making 12 payments of $357 every other Friday, totaling $4,284. Latoya agreed to pay the amount over a six-month period, and walked out of the store with cash and peace of mind.

Pay up, or else

Latoya made nine payments on time to the Cash Store before falling behind. As part of the loan agreement, she was required to make each payment in person; an 11-mile drive from her North Side home to the Grafton location. When Latoya couldn’t drive to the store one Friday in February because of a bad snowstorm, the Cash Store took the money directly from her account, and continued to make withdrawals, even when the full amount wasn’t available in Latoya’s checking account.

“They didn’t care if I had the money in my account or not,” said Latoya. “I explained to them I needed two weeks to catch up and I was told to refer to my loan contract. Eventually they kept drawing from my bank account three times a week, which caused me to accrue a $36 overdraft fee every time they attempted to debit the money from my account.”

Latoya spoke with a personal banker at PNC Bank. The banker sympathized with her and helped her close the checking account that the Cash Store kept drawing from, she said. PNC Bank even agreed to forgive the $1,700 in overdraft fees that Latoya racked up.

Once PNC Bank closed Latoya’s checking account, the Cash Store referred her account to a collection agency. Latoya now had to deal with harassing phone calls from debt collectors at home and work.

In May, one year after taking out the initial loan of $1,600, Latoya was sued by the Cash Store for $2,131. Because she didn’t show up for her scheduled court hearing after being notified of a pending lawsuit, the Cash Store won the case and began garnishing her paycheck to the tune of $190 every two weeks.

Four out of five payday loans are rolled over or renewed within 14 days, according to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). The majority of all payday loans are made to borrowers — like Latoya — who renew their loans so many times that they end up paying more in fees than the amount of money they originally borrowed.

Bourke found that the number one problem for borrowers in the payday lending market is unaffordable payments, which drives the cycle of repeat borrowing.

“A typical payday loan, when it comes due on the borrower’s payday, takes more than one-third of their check before taxes are taken out,” Bourke said. “Most people can’t sustain losing one-third of their next paycheck and still make ends meet, and it’s even worse when the typical payday loan borrower is a person that’s living paycheck to paycheck.”

Research conducted by CFPB in 2013 found that nearly half of payday borrowers take out 10 or more loans per year, paying fees on each loan rollover and new loan.

Change is coming

A big change is coming to the payday lending industry.

In 2016, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau will begin publishing rules to protect consumers from unfair and harmful loan practices. The rules are expected to prevent lenders from rolling over the same loan multiple times and to discontinue mandatory check holding. Check-holding requires the borrower to write a post-dated check for the money owed, or give written permission for the lender to automatically withdraw money from his or her personal bank account — whether the funds are available or not.

Under the new CFPB rules, payday lenders also would have to verify and evaluate a customer’s debt-to-income ratio, the same process traditional banks use. They would be required to take into consideration a customer’s borrowing history when deciding whether the borrower is able to pay back the loan and still cover basic living expenses.

“The payday lending market will be remade,” said Bourke. “We’ve been asking for stronger government regulations in this market, and the CFPB is listening and will put safeguards in place for borrowers that will ensure affordable loan payments, reasonable durations and reasonable loan fees.”

“These CFPB rules will create a new floor that all of the payday lenders will have to follow,” Bourke added. “But some problems will still be left on the table. The CFPB does not have the power to regulate pricing. It will still be up to the state of Wisconsin to regulate payday loan rates, if they choose to do so — and they should.”

For Latoya, new consumer protections can’t come soon enough. Latoya still owes the Cash Store $716, and is paying off the loan automatically every two weeks as a result of a court-ordered wage garnishment.

Asked whether she’d ever take out another payday loan again given her experience, she hesitated. “I hope to God that I don’t ever have to take out another loan. I’m going to try my best to avoid them, but if I do need the money I know it’s there.”

You can find other stories about Milwaukee's central city at Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service.