Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, perhaps the leading voice of uncompromising conservatism on the nation's highest court, was found dead Saturday, Chief Justice John Roberts has confirmed. Scalia, who had been staying at a luxury ranch in West Texas, was 79 years old.

"On behalf of the Court and retired Justices, I am saddened to report that our colleague Justice Antonin Scalia has passed away," Roberts said in a statement. "He was an extraordinary individual and jurist, admired and treasured by his colleagues. His passing is a great loss to the Court and the country he so loyally served."

In his 29 years on the court, Scalia achieved almost a cult following for his acerbic dissents, which in many ways shaped the ongoing legal debate over how courts should interpret the Constitution.

For decades Scalia railed against the Supreme Court's rulings on abortion, affirmative action, gay rights and religion. He lived to see many of the decisions he so reviled trimmed and even overturned after President George W. Bush replaced two conservative justices with even more conservative justices. But Scalia remained impatient with the pace of change. His influence continued, not by brokering consensus, but by goading his colleagues with biting dissents.

He was a fundamentalist in both his faith and his constitutional interpretation, according to former Solicitor General Paul Clement, a onetime clerk to Scalia.

"I think that he looks for bright lines in the Constitution wherever he can. I think he thinks that his faith provides him clear answers," Clement said, "and I think that's sufficient unto him in most areas."

A fine example of that was Scalia's landmark 2008 decision declaring that the Constitution confers on individuals a right to own a gun. The decision was greeted with cheers by gun enthusiasts, but denounced by police chiefs and big city mayors.

"We hold that the Second Amendment guarantees an individual right to have and use arms for self defense in the home," Scalia said in striking down the District of Columbia's ban on handguns.

Unanimous Confirmation

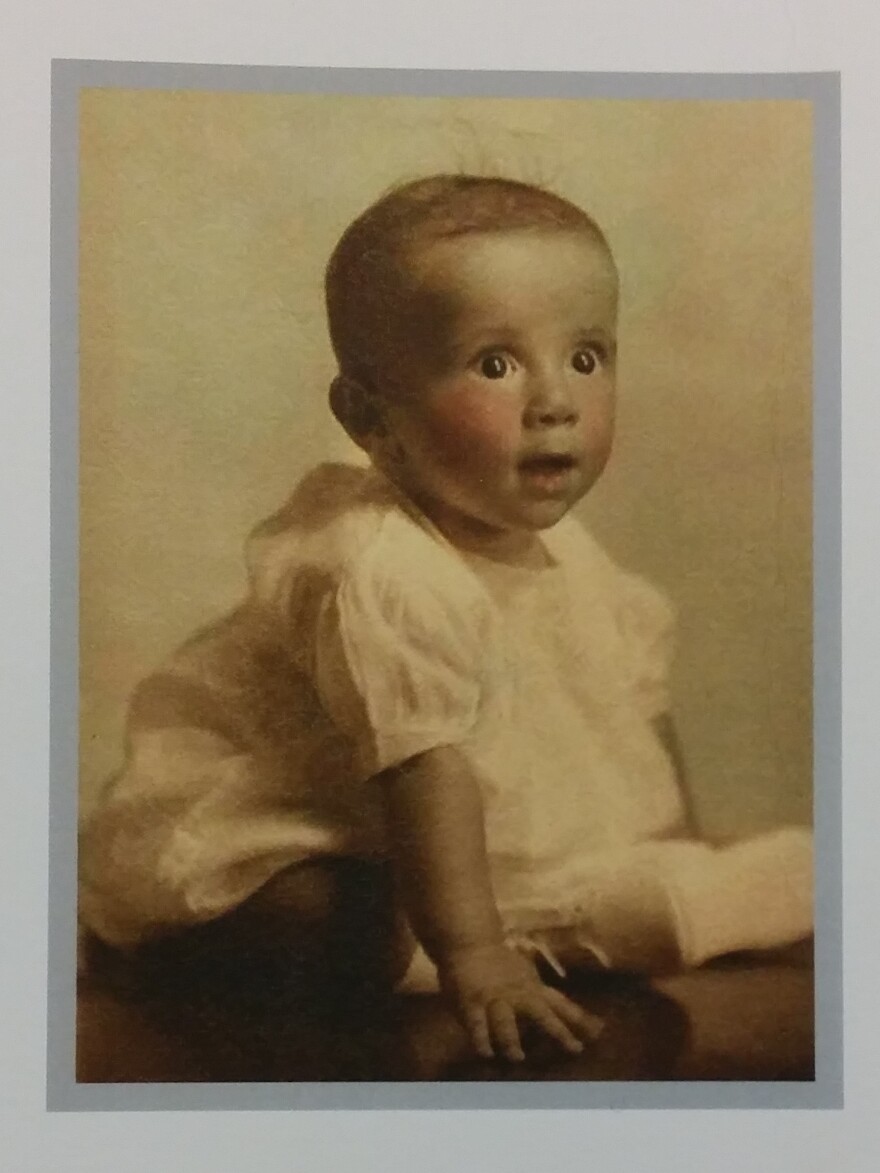

Scalia was born in 1936, the only child of a Sicilian immigrant and a first-generation Italian-American mother. Scalia, whose parents were both teachers, was educated largely at Catholic schools until he went to Harvard Law School, where he became editor of the law review. At Harvard, he met Maureen McCarthy, a feisty Radcliffe student with views as conservative as his. The two married and had nine children.

In the years after law school, Scalia at first practiced law, then taught it. But his love was politics and government, and he soon became a force to be reckoned with in Republican administrations.

Shortly after President Nixon resigned in the Watergate scandal, President Ford assigned then-Assistant Attorney General Scalia the task of determining who owned the infamous Nixon tapes and papers. Scalia decided in favor of Nixon, a reflection of his belief in a strong executive. But the Supreme Court ruled otherwise, and by a unanimous vote declared that the tapes and papers belonged to the government and the public.

Scalia returned to academic life when Democrat Jimmy Carter won the presidency, but when Republican Ronald Reagan succeeded Carter, Scalia was appointed first to the federal appeals court in Washington, and four years later, he was appointed to fill the Supreme Court seat being vacated by William Rehnquist, who was being promoted to chief justice.

That pairing turned out to be a lucky break for the quick-witted conservative. Democrats, in the minority in the Senate, could fight only one battle. Rehnquist's conservative judicial record was well known, while Scalia had only a four-year record, not to mention the fact that Italian-Americans were ecstatic about their first Supreme Court nominee. So opposition focused on Rehnquist, and Scalia skated to confirmation by a unanimous vote.

Once on the Supreme Court, Scalia almost immediately began pounding the table far more forcefully than the very conservative Chief Justice Rehnquist, particularly on the hot-button social questions. While Rehnquist, for example, consistently sought to overturn Roe v. Wade, the court's abortion decision, he sided with those who sought a buffer zone at abortion clinics to protect women from being harassed. Scalia vehemently disagreed.

"Does the deck seem stacked? You bet," he thundered. "The decision in the present case is not an isolated distortion of our traditional constitutional principles, but is merely the latest of many aggressively pro-abortion novelties announced by the court in recent years."

A 'Great Writer'

Scalia was a staunch advocate of free speech in general, surprising many when he provided the fifth vote to strike down laws banning flag burning.

Over the years he wrote many important majority decisions on the First Amendment and other topics — from property rights to environmental questions, gun control and states rights.

But, as legal scholar Cass Sunstein observes, like the great Oliver Wendell Holmes, Scalia will likely be remembered most for his dissents.

He was a hysteric in the cases that he cared about most.

"The thing to remember about Scalia is he was one of the great writers in the court's history," he said.

And he didn't pull his punches. When the court struck down a state law that made private homosexual conduct a crime, Scalia was outraged.

"It is clear from this that the court has taken sides in the culture war, and in particular in that battle of the culture war that concerns whether there should be any moral opprobrium attached to homosexual conduct," he said.

Sunstein says dissents like this one are illustrative of Scalia's Achilles' heel: "He was a hysteric in cases he cared about most."

And yet, as it turned out, Scalia was more right than his critics foresaw on one point. He was dismissive of the majority opinion's denial that it was supporting same-sex marriage. A decade later, same-sex marriage had been legalized in 13 states. And the Supreme Court, with Scalia in loud dissent, struck down a federal law that had denied federal benefits to legally married same-sex couples.

Scalia wrote with a sure pen. When the court, for instance, upheld the independent counsel law, Scalia alone dissented, declaring that the law would lead to unrestrained and politically driven prosecutions, a prediction that both Democrats and Republicans came to agree with when they refused to renew the law after the impeachment of President Clinton.

Constitutional Interpretation

On questions of separation of church and state, Scalia was a consistent voice for accommodation between the two, and against erecting a high wall of separation. When the court, by a 7-to-2 vote, struck down a Louisiana law that mandated the teaching of creationism in school if evolution is taught, Scalia was dismissive of evolution, calling it merely a "guess, and a very bad guess at that."

And when the court struck down a spoken prayer at a public school graduation, Scalia angrily dissented. The Founding Fathers, he said, viewed nonsectarian public prayers like this one as a mechanism for breeding tolerance and unifying people of diverse religious backgrounds.

"To deprive our society of that important unifying mechanism in order to spare the nonbeliever what seems to me the minimal inconvenience of standing or even sitting in respectful nonparticipation is as senseless in policy as it is unsupported in law," he said.

On death penalty questions, Scalia consistently dissented from decisions limiting its use, as he did when the court ruled unconstitutional the execution of the "retarded."

"The principle question," he said, "is who is to decide whether execution of the retarded is permissible or desirable? The justices of this court or the traditions and current practices of the American people? Today's opinion says very clearly, the former."

When the court struck down the death penalty for juveniles and pointed to what other countries do as evidence of what is considered cruel and unusual punishment, he dissented again.

"The underlying thesis that American law should conform to the laws of the rest of the world is indefensible. It is our Constitution that this court is charged with expounding. The laws of foreign nations and treaties to which this nation has not subscribed should have no bearing upon that exercise," he said.

Scalia's concept of constitutional interpretation became the focus of huge debates on the court and in the legal community. Is the Constitution a living document that adapts to the times, so that, for example, punishments once accepted could now be viewed as unconstitutionally cruel and unusual?

"The Constitution that I interpret and apply is not living but dead, or as I prefer to call it, enduring," he said. "It means today not what current society, much less the courts, thinks it ought to mean, but what it meant when it was adopted."

And since the death penalty existed when the Constitution was adopted, for instance, Scalia believed it could hardly be viewed as cruel and unusual punishment.

But Scalia's critics contended that there were some issues on which the justice ignored the plain meaning of the times. For example, on the question of affirmative action, proponents note that the framers of the 14th Amendment specifically approved measures that helped the newly freed slaves and not similarly situated white people.

Scalia, however, maintained he was a textualist, that in constitutional matters as in interpreting statutes, legislative history was immaterial. All that mattered were the words on the page.

More than anything else, Scalia was an advocate for bright lines in the law, lines that everyone could follow easily. He disdained the balancing tests advocated by more moderate conservative justices like John Marshall Harlan, Lewis Powell and Sandra Day O'Connor.

That meant that in some criminal law cases, he sided with defendants. In several cases involving the defendant's constitutional right to confront accusers, Scalia said that meant earlier recorded statements could not be substituted for real live witnesses being cross-examined in front of the defendant at trial. And in search cases, too, he drew firm lines, ruling for instance that police could not attach a long-term tracking device to a suspect's car without a warrant.

Even in some terrorism cases he was something of a purist, declaring that the administration of George W. Bush could not imprison an American citizen indefinitely without charge. On this, his opinion was the most radical on the court, rejecting the more equivocal and prevailing approach of other justices.

"If civil rights are to be curtailed during wartime," he insisted, "it must be done openly and democratically as the Constitution requires, rather than by silent erosion through an opinion of this court."

Such unexpected liberal moments, however, were rare. More often, Scalia's aggressive conservatism, even when it failed to prevail, often framed the debate, and justices once considered centrists came to be viewed as liberals compared with Scalia.

Pushing The Envelope

Scalia changed more than legal doctrine. When he came to the court, the justices asked few questions during oral argument. And Scalia, the junior justice, jumped in, pummeling lawyers relentlessly with questions. Soon other justices took a more active approach to questioning, so that most lawyers could get less than a sentence out of their mouths before being interrupted.

Witty and savagely funny, Scalia could also be bombastic and impolitic. In 2013, he referred to the Voting Rights Act as a law of "racial entitlements." On occasion, he could even alienate fellow justices. In 1989, for instance, when Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, a fellow Reagan appointee, deprived conservatives of a fifth vote to overturn Roe v. Wade, Scalia attacked her opinion as one that "cannot be taken seriously."

Comments like that lessened his influence. But Scalia happily observed that he looked to push the envelope, that if he had a 6-to-3 majority, he hadn't pushed it hard enough.

Sometimes when he pushed, his views prevailed. When they didn't, he took the fight to the printed page, knowing that his carefully crafted words would live to fight on long after he was gone.

Editor's Note: This story inadvertently failed to credit Oyez, a free law project at the IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law, for providing Scalia quotes from the bench.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxODc1ODA5MDEyMjg1MDYxNTFiZTgwZg004))