As Great Lakes delegates take another look today at Waukesha’s application to divert Lake Michigan water, they may consider an unsettled issue.

Two weeks ago, the so-called Regional Body held a marathon session in Chicago and seemed to agree that Waukesha should trim down its proposed service area closer to the city’s boundaries. During the discussions, one question arose intermittently.

The question that left some representatives scratching their heads: Has Waukesha’s deep pumping of wells already drawn in water from Lake Michigan?

Michigan delegate Grant Trigger says, yes. “Everything that Waukesha pumps they discharge to the Fox River in the Mississippi River Basin,” he says.

So he says approving Waukesha’s application could reduce the amount of Great Lakes water it’s currently sending into Mississippi River Basin. “The analysis performed by the USGS and the Southeastern Planning Authority concluded that there is so much water pumped by Waukesha that they are literally bringing water in from Lake Michigan into their wells,” Trigger says.

That's false, according to USGS hydrologist Daniel Feinstein.

He was part of a team, along with the Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey, that modeled groundwater conditions in the southeastern Wisconsin region.

“Even if you pumped it at much higher rates, you’d have to pump for a thousand years or more before you would actually get water from Lake Michigan coming out of the wells,” Feinstein says.

He says the team looked back from the late 1800s through 2000. Heavy well pumping began after World War II.

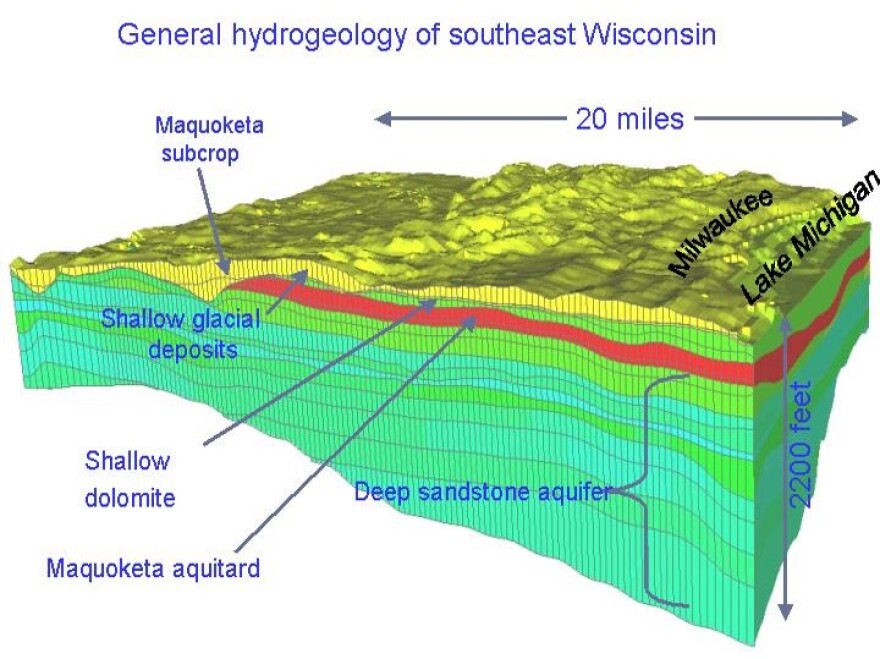

Feinstein says Waukesha’s operation has represented only a fraction, about 25 percent, of the total deep pumping within the region. “If we’re talking about water coming out of the wells now, none is from Lake Michigan proper. It’s very far away and kind of armored by a shale bed the famous Maquoketa Shale,” he says.

However, Feinstein says all of the pumping region-wide has impacted how groundwater travels. “Water that under natural conditions flowed toward Lake Michigan, some of it is being reversed where it’s curling back. It was flowing toward Lake Michigan maybe under Milwaukee County and now it’s curling back,” he says.

So right now, what’s the impact to the Great Lakes Basin and Lake Michigan? “It’s non-detectable,” Feinstein says.

Whether detectable or not, Peter Annin thinks the Lake Michigan seepage issue will play a role in the final Waukesha decision.

Annin authored the book The Great Lakes Water Wars, and has been observing every step all of the deliberations.

“It’s one of the central points, it’s not the central point, but the reason that the jurisdictions, or at least some of the jurisdictions are emphasizing that is that it actually narrows the precedent that’s being set,” he says.

If decision-makers determine Waukesha has already influenced the Great Lakes Basin’s groundwater, “that narrows the precedent in the future, potentially, that are also having that similar negative impact on a Great Lake because of their groundwater withdrawals,” Annin says.

No one can know what each Great Lakes delegate is weighing as he or she considers Waukesha’s request.

The Regional Body plans to issue its recommendations at meetings in Chicago May 10 and 11.

The final decision rests with the Compact Council – all 8 Great Lakes States must vote yes in order for Waukesha to tap Lake Michigan. That vote is slated for June 13th.