Segregation in metro Milwaukee can be traced back, in part, to discriminatory housing practices like redlining and racial restrictive covenants. During the Civil Rights movement, there was large-scale pushback against such practices.

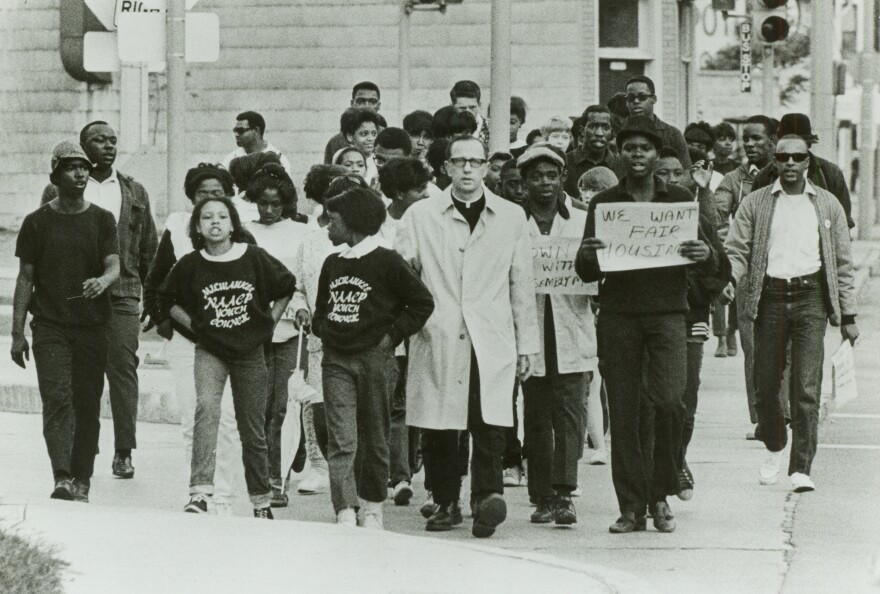

The 1967 March on Milwaukee led by Father James Groppi and the NAACP Youth Council helped, in part, contribute to the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which prohibits housing discrimination based on race, among other categories.

Civil rights activist, poet and playwright, Margaret Rozga, was a college student in Milwaukee during the height of the Civil Rights protests.

Although she grew up somewhat sheltered on the city's predominantly white and Catholic south side; as a young adult, she saw news stories about about the beatings of marchers in Selma, Alabama, and the murder of three Mississippi civil rights workers.

Rozga, now professor emeritus of English at the University of Wisconsin-Waukesha and widow of James Groppi, explains that these events inspired her to go to rural Alabama for a voter registration project in the summer of 1965.

"The idea was that a group of northern volunteers would adopt a county in the south and work there. We were an integrated group, and [upon return to Milwaukee] I had friends who lived on the north side," she details. "To get from where I lived to where they lived was complicated."

She joined the local NAACP Youth Council because "I felt like I would be a hypocrite if I had volunteered in the south and then came back and did nothing."

At that time, the Youth Council, headed by Father Groppi, was pushing for stricter enforcement of the building code. Groppi was taking schoolchildren down to the Milwaukee Circuit Court to watch the trials of landlords who were renting properties in the inner city and not keeping them in good repair.

"There was one case in particular of a landlord who had over 100 properties with building code violations. On all of them he was found guilty, but the penalty was $1. So there were no financial or legal repercussions," she says. "It was a lot cheaper to let the building code violations exist than it was to fix them."

Rozga explains that there was a vested interest in maintaining segregated housing. "Segregated housing was a boon for property owners and real estate companies. You had a rapidly growing African-American population and a limited housing supply," she explains. "[It comes down to] the law of supply and demand, the price is going to go up, and the quality doesn't have to go up. So, people were making a lot of money."

Councilwoman Vel Phillips, the first African-American and first woman on Milwaukee's Common Council, had proposed an open housing ordinance in 1962. And in 1966, the NAACP Youth Council decided to back Phillips' efforts, shifting its focus from building code violations to supporting Phillips push for the law.

Rozga says this realignment came about because of Ronald Britton, an African-American Vietnam vet who had returned from service and tried to rent an apartment for himself, his wife and his 10 month old daughter. Britton was told by the property owner that the place was already rented, but when they looked into it further, the property owner admitted that they couldn't rent to him because, as Rozga says, "'what would [the] neighbors think?'"

"If they hadn't had a 10 month old daughter, maybe they just would have gone on," she assesses, "but I think that one of the things that happens is you look at the next generation and you say 'no, this can't go on.' We can't have our children face the same problems we faced, and so they asked the Youth Council for help."

The Youth Council began picketing aldermen with African-American constituents who had been voting against Phillips' proposal. On August 28, 1967, fair housing protestors decided to march from the Youth Council headquarters, the Freedom House on the north side, across the 16th Street viaduct into Milwaukee's nearly all-white south side.

"When we got to the south end of the viaduct, there were huge crowds of counter demonstrators," she details. "The police estimated 5,000-8,000 people."

Rozga says that even the police admitted that the white people were out of control.

"By the time we got to the viaduct, what I remember is holding the poster board, paper really, over my head to keep myself from being hit with bottles and rocks and whatever else was being thrown," she explains. "By the time we were on 16th and National, we were running [back] for the viaduct."

>> The violence that ensued can be seen here

From the summer of 1967 to the spring of 1968, there were a steady stream of developments. After 200 continuous nights of marching in Milwaukee, the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on April 4, 1968, and nationwide memorial demonstrations in his honor, the protestors got what they wanted with the Fair Housing Act, part of the Civil Rights Act of 1968.

Rozga admits that the feeling of success was short lived. "[After the passage of the law] the fathers of African-American youth council members worked at places like A. O. Smith. The work may have been hard, but they were earning enough money to send their children to college," she recalls. "It was like a door opening and a number of people went through that door, and then the jobs moved out of the city and the door slammed shut."

Writing has been a way for Rozga to share to her activism. She has written March On Milwaukee: A Memoir of the Open Housing Protests, as well as a book of poems about the experience, called Two Hundred Nights and One Day. "Intrinsic to the story is that potential to empower people," she says.

"When you preach the gospel of inclusivity, when you talk about fairness, when you talk about respecting people's rights, when you emphasize the positive about what we would like our city, our state, our country, our relationships with each other to be, people respond...love is more powerful than hate," she concludes.