Historically, the wood from the dead or diseased trees lining city streets has been chipped, chopped or simply dumped.

The U.S. Forest Service estimates that urban wood waste could produce 3.8 billion feet of lumber annually. That amount would be about 30 percent of all the hardwood lumber the U.S. produces annually.

A local movement is growing to resource the logs - to produce everything from flooring to furniture.

Just over a year ago, Bob Wesp walked me through a tangle of urban trees outside his mill in Hartford. Bob and his brother Jim were taking in about 4,000 felled trees a year – most from the City of Milwaukee. At the time, the family’s urban wood sales amounted to barely a trickle.

Today, Jim Wesp says the company displays urban along with the traditional lumber in its showroom, and sales are growing.

“I would say that we’re at about the 10 percent range,” he says.

That’s 10 percent of the Wesps' total lumber business.

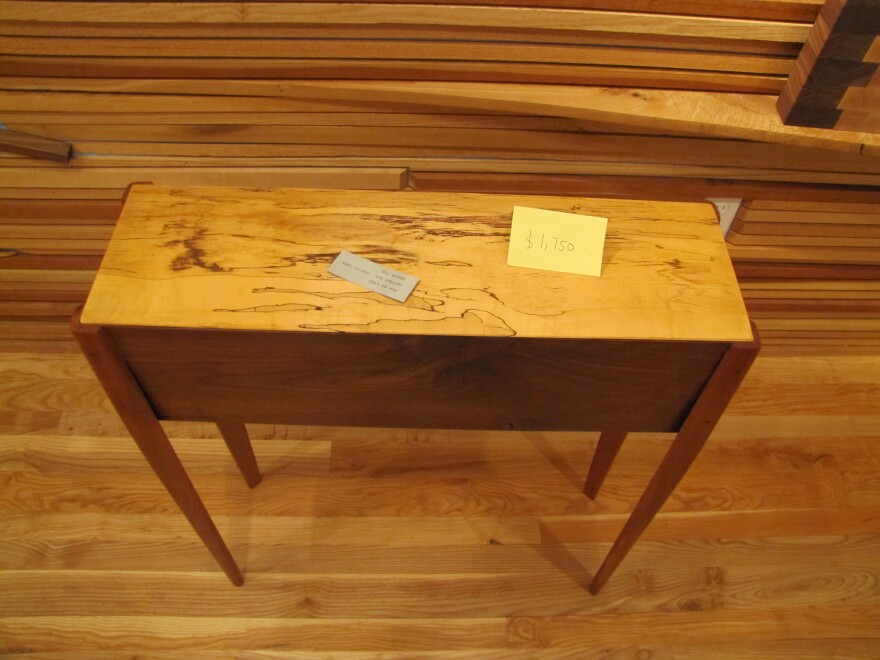

Jim Wesp says among the customers who’ve ordered urban wood products are a new child care center and a grocery store, but “most of the urban projects that we have been involved in have been [individuals] - a customer who says I want to build a dining room table.”

The reason city wood may appear to lend itself to smaller projects is because trees from the urban canopy are often diseased or damaged. You might find a nail or metal impaled beneath its bark, and it can take time and attention to salvage what’s best.

At 61st and Bluemound, August Hoppe stands in his brand new, urban wood showroom.

Hoppe has expanded the tree service business his grandfather, dad and uncle launched in 1972.

“For years ,what we did was just do what conventional tree services did and try to get it off the job site in the most efficient fashion," he says. "So that often meant cutting it into small pieces and hauling it off. But over the years, people had asked me, ‘what are you doing with all of that wood.'"

Now, rather than simply pulverizing or hauling away a city dweller’s tree, Hoppe offers the option of fashioning the trunk into a table or mantel.

“A tree that will have knots and limbs that have grown off of the trunk, those often provide beautiful slabs because they showcase the grain and the character of the wood," he says.

Hoppe is less than a year into processing urban lumber at his mill in Grafton, yet he plans to expand the operation. He even just purchased something called a knuckleboom crane. The truck allows him to haul in even larger city logs.

He hopes to create demand and consistent inventory to feed it.“Work with municipalities and other tree services to really grow this trend and be a collection for logs and really help jumpstart the movement to make it grow. And where it ends up, I don’t know,” Hoppe says.

Dwayne Sperber is an urban wood craftsman and advocate. He says while encouraging the movement, he’s tried to be strategic. “If anything, I’ve held the reins back so that this industry could evolve,” he says.

Last year, the DNR awarded Sperber a grant to cultivate a wider market for city lumber. He’s helped form a nonprofit group called Wisconsin Urban Wood - now 18 members strong.

He recently convinced a well-established wood flooring company to carry urban wood. “They’re not just going to jump into this," Sperber says. "We have learned, evolved and here we are.”

Sperber freely admits he keeps on lumber types, until they agree to talk urban wood with him. The Wesps are on board, so are the Hoppes.

“We really are committed to the whole notion that a viable business plan can be made from this,” Jim Wesp says.

August Hoppe says his company is looking at trends. “Even though we haven’t been around very long, we know what’s in demand," Hoope says. "And with our partners, it’s kind of funny because one of them comes from a lumber background and one from a craftsman background and we’re at a point where we’re fighting over the log, saying no, I want it.”